It is with this enigmatic sentence that one of my Japanese mentors introduced the growing difficulty with continuous improvement.

What it means is that at the beginning of an improvement program or when starting in a new area, the first and usually the easiest actions bring big improvement, hence the “easy” 50%.

This is also known as “reaping the low hanging fruits“, another metaphor for earning easy, spectacular results with very reasonable effort.

Once these easy and quick wins are done, what is left to improve requires more effort, more time or more investment.

The improvement curve is therefore asymptotic and it is increasingly difficult and expensive to squeeze out the last improvement potential, hence the “difficulty to improve (the last) 5%”

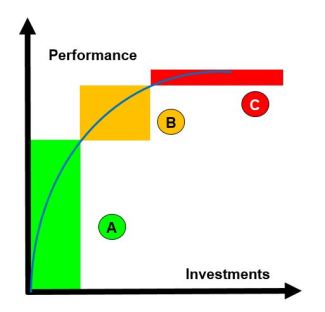

The graph shows the 3 stages of improvement

A: quick and easy, few actions, visible results, big leverage, usually a leap in performance. Excellent Return On Investment (ROI).

A: quick and easy, few actions, visible results, big leverage, usually a leap in performance. Excellent Return On Investment (ROI).

B: second stage in continuous improvement, more effort and investment is necessary, but the ROI is still worth it

C: “chasing the decimals” : huge efforts and investment are required to squeeze out the last potential. The ROI is not worth it.

At some point, the Return On Investment (ROI) is not worth going on. This means that improving further what exists and/or the way it has been done until now is no more meaningful. What is required is a breakthrough, a radical change.

This is where kaizen (continuous incremental improvement) must give way to kaikaku (radical change), or in other words: as the old process or usual way cannot be further reasonably improved, it must be totally reconsidered.

Yet in many cases this is the upper limit of improvement as the process cannot be changed. Too often redesigning the product or process is not possible:

- Design has to be approved or the new product/process has to undergo lengthy and costly qualification (pharma, automotive, aerospace…)

- Remaining life is not long enough to pay for

- Facilities are not flexible, can’t be modified

- The modification would break some contract

The continuous improvement is often limited by options and decision made in early design and development stages, a fact I discuss in >this post<

Related: Stuck with continuous improvement?

Pingback: Improving 50% is easy, improving 5% is difficult | Ryan Stoner

Pingback: Improving 50% is easy, improving 5% is di...

Pingback: Improving 50% is easy, improving 5% is difficult | Michel Baudin's Blog

Hi Chris,

Yes, this phenomenon can be seen in any number of place… But, by my experience, it’s most prevalent in work that NASA did early on in the “Space Race;” whereby NASA engineers observed that the closer they progressed toward a target state of “perfection” the more rapidly (exponentially to be specific) the costs of pursuing that next incremental level escalated. In addition to NASA’s observed and documented experience, the same phenomenon occurs anywhere and everywhere a “SYSTEM” is pushed toward perfection.

Having made that last statement, there are likely some very sharp CI practitioners that will argue against its truth/reality on the basis of what Toyota (via the TPS/Toyota Way approach in general and the on-going practice of kaizen in particular have been able – and continue to be able – to achieve in the way of consistently superior performance. From my POV, it’s OK to make such an argument, BUT it does not – IMO – reflect the realities of what actually enables Toyota to stay on the forefront the [efficiency and effectiveness-based/driven] competitive frontier…

What I see as not being taken into consideration is the point at which the cost of pursuing the next one, or two or some small number of incremental improvements justifies pursuing a more dramatic effort directed at a breakthrough (aka game-changing) improvement of the kaikaku-type. A good example of where these sorts of initiatives have clearly taken place inside of Toyota include the development and introduction of the FBL (Flexible Body Line) in the early to mid-80’s, and then – 17 years later – the development and introduction of the GBL (Global Body Line) in the early 2000’s. What I see as being a key take-away from this sort of kaikaku-punctuated evolution of the TPS/Toyota Way is the need to reset the “baseline” for what constitutes the theoretically achievable level of operational excellence for the entire SYSTEM. And once a new baseline has been set, it then becomes possible to return to the application of the on-going practice of kaizen, or pursuing incremental, cost-effective improvements that move the SYSTEM closer to its theoretical maximum performance potential. Ergo, the dual practices of both kaizen and kaikaku MUST function together – as in the YIN and the YANG – in order for Toyota (or any other similarly capable organization) to continually pursue the highest-order level of operational excellence under any given set of conditions and circumstances.

Bottom line: YES…“Improving 50% is easy, improving 5% is difficult”… BUT RESETTING THE BASELINE FOR WHAT’S POTENTIALLY POSSIBLE CAN BE A CHALLENGE/PROBLEM OF THE “WICKED” TYPE.

[Note: I’m borrowing the term “WICKED” from the SYSTEMS-THINKING handbook vernacular and, more recently, in keeping with how it is used by Dr. Derek Cabrera – the developer/originator of the notion of D.S.R.P.-THINKING skills – in his most recent book entitled: “Systems Thinking Made Simple New Hope for Solving Wicked Problems,” Solving problems of the “WICKED” type seems – to me – to be something that Toyota also does far better – and more consistently – than any of its competitors.]

LikeLike

Thank you Jay for your (impressive) comment and for sharing your testimony. I totally agree with you and plan to post a sequel about what you call “reset the baseline”.

Kind (Parisian) Regards

LikeLike

Hi Chris,

Please be advised, when it comes to “resetting the baseline,” there’s more to it than just adjusting performance metrics. It’s in good measure where that “WICKED” part comes from. Again, by my experience, there are a number of critical “discontinuities” that need to be addressed (ideally anticipated) and dealt with in order to help ensure the least amount of waste is being generated in the process.

Best, Jay

LikeLike